Who’s up and who’s down in the K-shaped economy

Food and energy prices are a big part of the affordability problem, but the biggest factor keeping lower-K Americans down is probably soaring housing costs.

Key takeaways: 😉

New research identifies who is harmed most by the K-shaped economy, in which there’s a large gap between those getting ahead and those falling behind.

One problem is that elevated inflation of the last five years hits lower-income Americans hardest, even now.

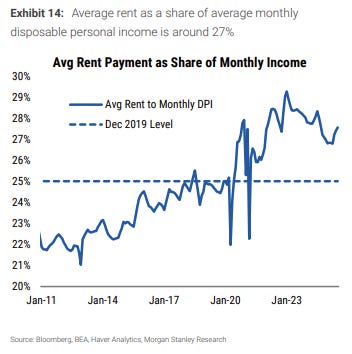

Housing costs consume a much larger portion of the typical paycheck than they did just five years ago.

2021 was the cutoff point to buy a home and cash in on low interest rates and reasonable prices.

Baby Boomers are far more likely to live in the upper-K economy, while Millennials and Gen Zers are stuck far below.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Are you upper K or lower K? These are the haves and have-nots of the 2020s, and lower-K Americans are rightfully demanding attention as they struggle with high costs and stagnant living standards.

There’s always stratification in the US economy. But three developments have made the K-shaped economy especially pernicious for those on the bottom. One is the Covid pandemic that began in 2020 and involved extreme stimulus measures enacted by the Federal Reserve. Another is the elevated inflation of the last several years. The third factor is ongoing digital transformation of the economy, which can block the path to prosperity for lower-skilled workers.

The result is an affordability problem that doesn’t show up neatly in the aggregate data but is hammering lower-K Americans, anyway. “The affordability discussion ties in closely to the K-shaped economy,” researchers at Morgan Stanley wrote in a recent study. “Low-income consumers have faced more pressures given that they tend to experience higher inflation rates. We also highlight young consumers and renters/recent homebuyers as groups more exposed to affordability challenges.”

[More: How to survive America in 2026]

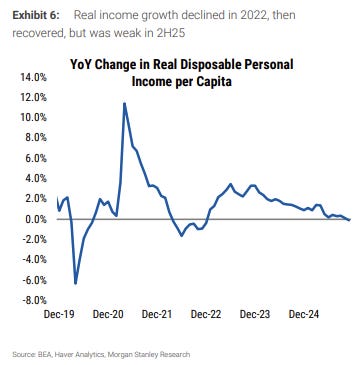

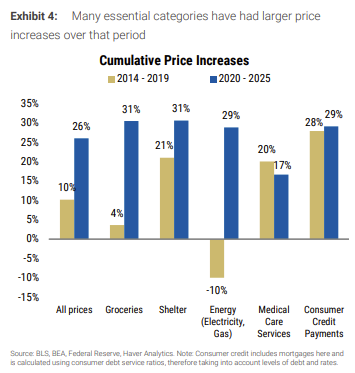

From 2020 through 2025, overall prices rose by 26%. The cost of groceries and housing each rose by 31%. Energy costs rose by 29%. Those increases were sharply higher than during the prior six-year period. Lower-income Americans spend more on necessities, which means inflation hits them harder. Most prices that went up stayed up. Incomes caught up with inflation in 2023 and 2024, but income growth has been slowing, which is why inflationary pressures remain.

Inflation pressures get a lot of attention and are well understood. Less clear are the effects of Covid-era Federal Reserve policies that slashed long-term interest rates. That was a windfall for Americans who owned homes prior to Covid. Many of them refinanced mortgages at record-low rates, saving thousands of dollars per year. Low rates triggered a buying binge that pushed home values far higher, increasing real estate wealth for owners.

But policies that benefited home owners punished hopeful buyers a few years later. Home affordability is now at the worst levels since the peak of the housing bubble in 2006, according to the Atlanta Federal Reserve. In 2019, it took 29% of median income to pay for a typical home. Today, it takes 43% of median income. Higher home values pass through to the rental market, one reason rents have risen by more than incomes since 2020.

[More: Why Americans say they’re worse off under Trump]

If the economy were healthy at all levels, workers would be catching up. But while GDP growth is solid, that is mostly coming from the artificial-intelligence boom, which creates some temporary construction jobs but not a lot of employment after that. And many analysts think AI will ultimately replace a lot of jobs.

We may be in the early stages of that. Job growth slowed sharply in 2025, with the economy losing 67,000 jobs during the last three months of the year. Real incomes, adjusted for inflation, have been flatlining, especially for low-income workers, who are barely staying ahead of inflation. People hit the hardest by the last five years of elevated prices are not digging out.

[More: Let’s grade Trump’s affordability plans]

A key factor landing people in today’s upper-K economy is whether they bought a home before Covid and benefited from refinancing opportunities and soaring home equity. The before-and-after cutoff point, roughly speaking, is 2021, when home prices started to spike. JPMorgan Chase estimates that a typical home buyer in 2024 had to spend 45% more of their income on mortgage payments than a buyer in 2019. That’s a huge gap that ought to be a three-alarm emergency for policymakers, but, alas, is not.

It goes without saying that workers with higher incomes and more financial wealth are comfortable residents of the upper-K economy. The Morgan Stanley research goes further by highlighting some of the factors that keep lower-K Americans stuck there and prevents them from moving up.

Younger Americans tend to have weaker credit scores, which means they face higher interest rates when they take out a loan or carry a balance on a credit card. And those interest rates have gone higher in recent years. Younger Americans are also more likely to be renters. Not surprisingly, President Trump’s approval rating has dropped by more than 30 points among young voters, while remaining stable among older ones.

So the upper-K economy skews toward older Baby Boomers and includes those who have owned a home for five years or more and have some financial assets, as well. The lower-K economy skews toward Millennials and Gen Zers and includes those with credit-card debt and burdensome student loans. The biggest change of the last several years are new financial barriers to home ownership, coupled with soaring rents, which makes it hard for millions of workers to save money, given that housing eats so much of their paycheck.

How many Americans are stuck in the lower-K economy? It’s hard to estimate, because there’s a lot of overlap among people dealing with financial struggles. Federal Reserve data shows that the bottom 50% of households—around 67 million homes—have very little financial or real estate wealth. That could add up to 100 million adults living in those homes, which is more than one-third of the adult population. That tally includes a lot of young people who might not mind being behind if they saw a path forward. But many just watch the rent devour their paycheck and wonder why they’re getting screwed.

The confines of the lower-K economy don’t have to be permanent. Rents and home prices are slowly easing and a bit of relief might arrive this year and next. Policymakers at all levels of government could take steps to build more housing, lower health care costs, bring more energy online and make other things cheaper. But government moves slowly, and it’s not clear many elected leaders even get the problem. The K-shaped economy, sorry to say, has legs.

Thinks Rick. I really like the Pin Point Press.