Why stocks are soaring while the economy slows

It could be a bubble. But there's new demand for US stocks from some of the richest investors on the planet.

The stock market is not the real economy, the axiom goes. It may be truer than ever now.

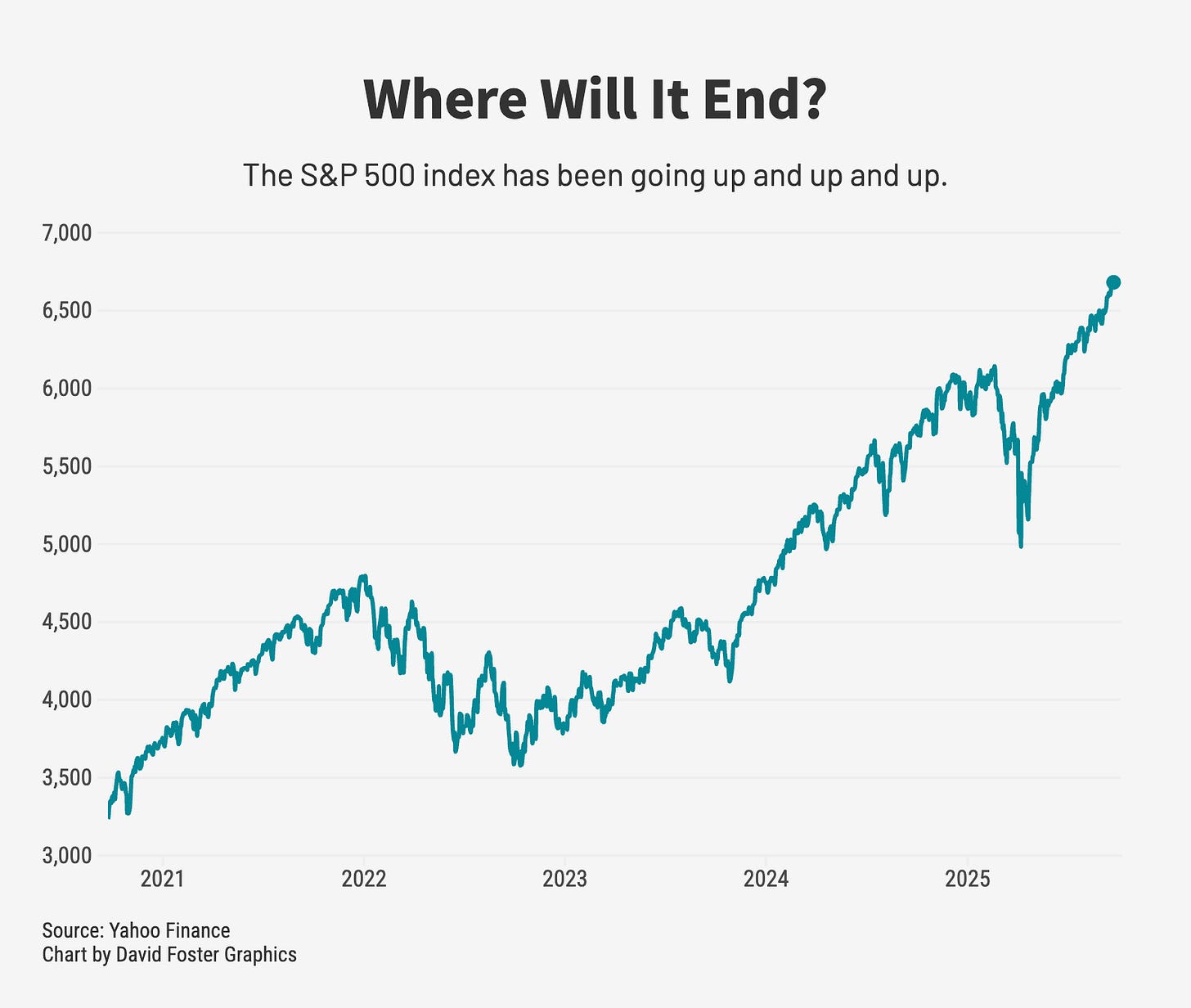

Stocks have been on a tear for five months, with the S&P 500 index up 30% since late April. Federal Reserve interest rate cuts and the artificial intelligence boom explain some of the froth. Look at the recent trend in this David Foster chart:

But stocks are overvalued by historical measures, and the overall economy may be weakening. Job growth is slowing to a crawl, which is why the Fed is cutting interest rates. The Trump tariffs are beginning to push prices up and dent consumer purchasing power. One key forecasting group thinks US economic growth will slow from 2.8% last year to just 1.8% in 2025, and an even lower 1.5% in 2026.

At some point, a slowing economy normally cuts into corporate profits and brings stock back to earth. “The recent runup in equity valuations is a red flag that a correction could be in the making,” Joe Brusuelas, chief economist at RSM, wrote on September 23. He cites technical factors that are in place now and normally precede a correction, which is a drop in stock values of 10% to 20%.

Yet US equities have some unusual sources of support these days that may keep stocks buoyant even if the economy falters. Economist Mehmet Beceren of Rosenberg Research cites several factors that are “decoupling” US stocks from the real economy. First, he points out that huge tech companies dominating stock indexes these days, such as Alphabet, Apple, Microsoft and Nvidia, tend to perform well even when other stocks decline. That’s because those businesses have massive global scale and provide services businesses and consumers want even during downturns.

Second, there’s a new phenomenon in which these companies are so large and diversified that global investors consider them a form of safe asset, similar to highly rated government bonds. “Mega-cap tech firms, with trillion-dollar market caps and indispensable products, are treated as safe assets by sovereign wealth funds, and even by central banks,” Beceren wrote in a September 18 analysis.

The Swiss National Bank, for instance, holds around $167 billion worth of US equities, including $42 billion in the stock of Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft and Nvidia. The Swiss government, which owns the bank, doesn’t buy stocks as a speculative venture. Instead, it buys dollar-denominated assets to manage the value of the Swiss franc when the dollar is relatively weak and the Swiss franc is relatively strong. Sovereign wealth funds, which are state-owned investment vehicles managed by rich countries such as Norway, Abu Dhabi and Kuwait, also seem to be buying more shares of America’s tech behemoths.

These deepest-pocketed investors are becoming a crucial source of demand for shares in America’s biggest companies, and demand for stocks is one factor that helps keep equity prices high. But this doesn’t mean stratospheric valuations can last forever.

Tech stocks tend to do better when interest rates are falling, or when investors expect them to fall. That’s because these companies innovate and invest a lot of money, much of it borrowed. Lower rates make the future cost of money cheaper for these companies, boosting their future cash flow.

But rising rates can have the opposite effect, and in fact the tech sector slumped from early 2021 to early 2022, when investors were expecting future rate hikes that materialized starting in March of 2022.

The Fed just started a rate-cutting cycle, which investors expected. So that’s good for tech stocks now. But when investors start to think rate cutting is over and rate hikes might be in the cards, that will work against tech valuations.

Inflation expectations are another wild card. The Fed has started cutting rates with inflation close to 3%, which is considerably higher than its preferred level of 2% or so. If investors start to think the Fed is willing to tolerate higher inflation to boost the job market—or to appease President Trump, who wants to strong-arm the Fed into sharp rate cuts—then long-term rates will probably rise.

The market sets long-term rates, through the return investors demand to commit their money by buying bonds. If they think future inflation will be higher, they’ll require a higher rate to lock up their money and compensate for the risk inflation will erode its value. Higher rates will hurt tech valuations whether they come from monetary policy or market movements.

So stocks that are unusually buoyant today will need favorable conditions to stay that way. “The US stock market is more sensitive to interest rates … yet less sensitive to the US economic cycle,” Beceren writes. Maybe that’s good. But maybe it isn’t.