Trump’s inflation problem goes well beyond tariffs

Energy and services costs are up, with tariffs likely to make inflation worse later in the year.

Every month when the inflation numbers come out, economists hunt for signs that President Trump’s import tariffs are driving up prices. There are some indications of that. But the bigger story, for now, is inflation coming from other sources.

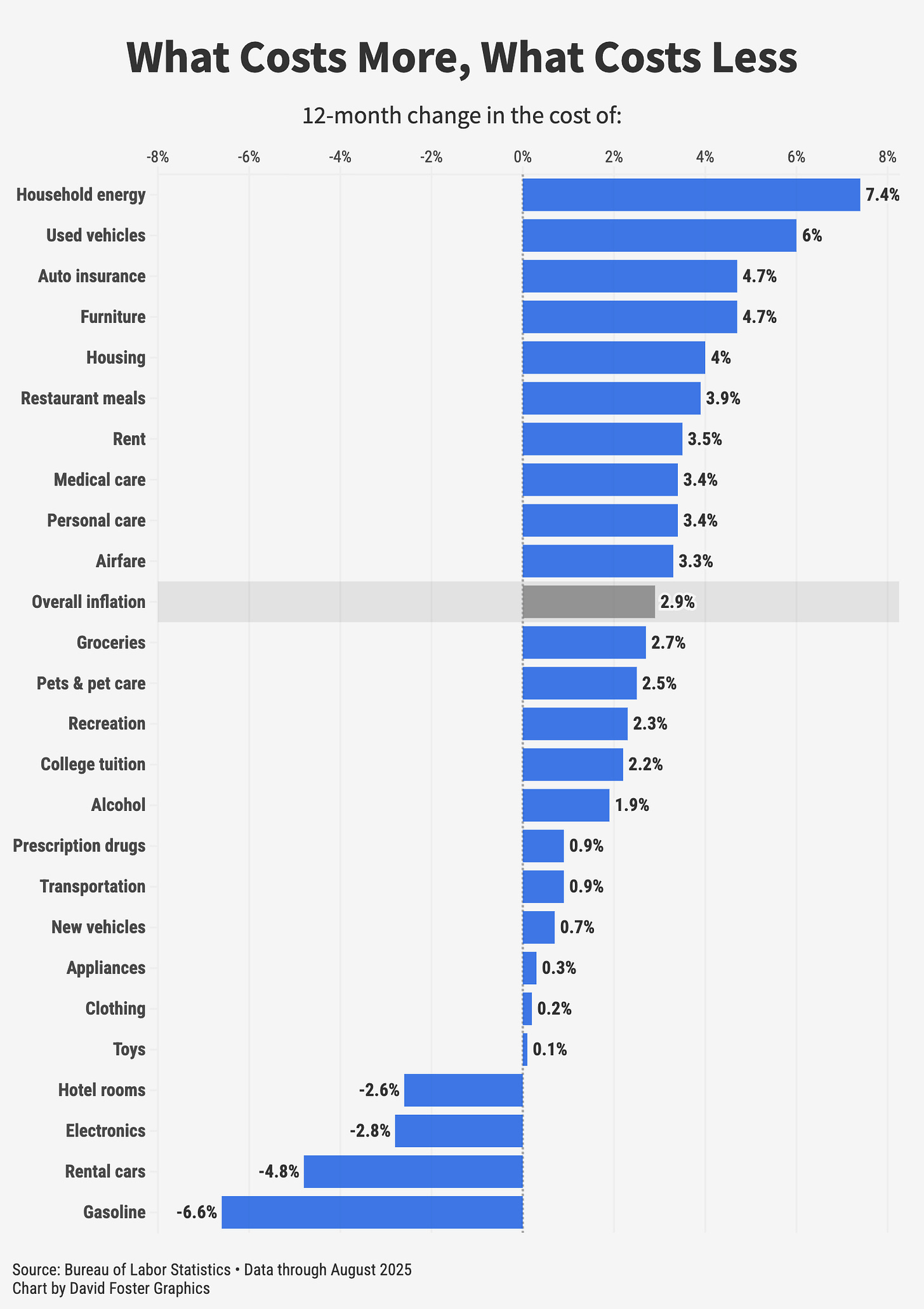

The year-over-year inflation rate rose from 2.7% in July to 2.9% in August, validating many economists’ concern that inflation is heading up, not down. The Federal Reserve is likely to cut interest rates soon, but rising inflation makes that more difficult because lower rates can stimulate spending and make inflation worse.

To understand where inflation pressures are, and aren’t, graphics guru David Foster and I have been making a version of the following chart every month since 2022. The categories at the top, with the highest rate of year-over-year inflation, have typically been things that jumped in price because of temporary shocks or unusual scarcity, such as gasoline, automobiles, and car insurance. After the shock, inflation in those categories moderated.

Look at the biggest jump in annual inflation now: Household energy. That’s mostly electricity, with the annual inflation rate jumping from 2.3% in January to 7.4% now. Energy is getting more expensive because we’re using more of it. Data centers powering artificial intelligence are energy hogs, and electric cars and trucks that charge off the grid add to demand, as well. It’s costly and time-consuming to build new power plants and connect them to the grid, which means high energy inflation is likely to persist.

Americans spend about the same amount of money on household energy as they do on gasoline. But the cost is much harder to see than the pump prices advertised at every gas station in America. People certainly feel the pinch when summer air conditioning or winter heating sends their bills soaring. But convoluted utility statements make it hard to tell what, exactly, is getting more expensive, and by how much.

As for tariffs, there were some signs of it in the August numbers. On a month-to-month basis, there were unusually large jumps in the price of cars, clothing, appliances and home improvement materials, categories where imports represent a large share of spending. But annualized inflation in most of those categories is restrained, as the chart above shows. “While the tariff pass-through has been modest, there has been some,” economist David Rosenberg of Rosenberg Research wrote in a Sept. 11 analysis.

Services are still a bigger driver of overall inflation than goods, and services are generally not subject to any Trump tariffs. Year-over-year services inflation is 3.9%, while annualized goods inflation is just 0.2%. That’s a continuation of the longer-term trend. The initial inflation shock in 2021 and 2022 was soaring prices for goods, as stimulus checks and Covid shut-ins led to a surge or people buying stuff. But goods prices moderated as the Covid pandemic ended and Americans began to shift back to spending on services. That sent services prices higher.

One surprise in the August numbers was a big month-to-month jump in restaurant prices, with no obvious explanation. It’s possible that the Trump tariffs are raising food costs and restaurants are passing it along to customers. But dining out counts as a service, so that’s another source of inflation not technically related to tariffs.

Economists still expect tariff-related inflation to become more tangible in coming months. If energy and services inflation remain more or less as they are, that could push the overall inflation rate to the range of 3.5% or maybe even 4%. That’s not nearly as bad as the 9% inflation in 2022, but consumers have inflation fatigue and they want to see falling prices, not smaller increases. Whether tariffs are the cause or not, Trump has some explaining to do.