The Fed rate cut won’t help most people

Fed rate cuts get wall-to-wall coverage but don't do much for ordinary workers.

Wall Street and the financial media obsess over Federal Reserve interest-rate decisions. The Fed’s policymakers meet eight times a year and announce any change in rates at 2 pm on a Wednesday. Every Fed watcher clears the schedule on Fed day to parse every letter of every word the Fed chief says or doesn’t say following the decision.

So it seems like a big deal that the Fed cut interest rates by a quarter-point on September 17 for the first time in nine months, while signaling that further rate cuts are coming. The story gets juicier because of President Trump’s efforts to seize control of the world’s most important financial institution and dictate the direction of interest rates for political reasons, which he hasn’t quite been able to do yet.

For all the hype, however, Federal Reserve rate cuts won’t directly affect the borrowing rates most people pay, or save business and consumers money any time soon. “For most Americans, a quarter-point rate cut is not that important,” Joe Brusuelas, chief economist at RSM, wrote on September 15. “Remember that the realities of Main Street are quite different from those on Wall Street.”

That’s because the connection between the short-term rates the Fed controls and the longer-term rates affecting mortgages and most other loans is more tenuous than it used to be. It’s even possible most loan rates will rise as the Fed cuts short-term rates.

The Fed controls short-term rates banks pay to each other for overnight lending, which is a key part of the nation’s financial plumbing. Lower short-term rates normally bring down longer-term rates as well, especially if the Fed has indicated it plans to cut rates for a while.

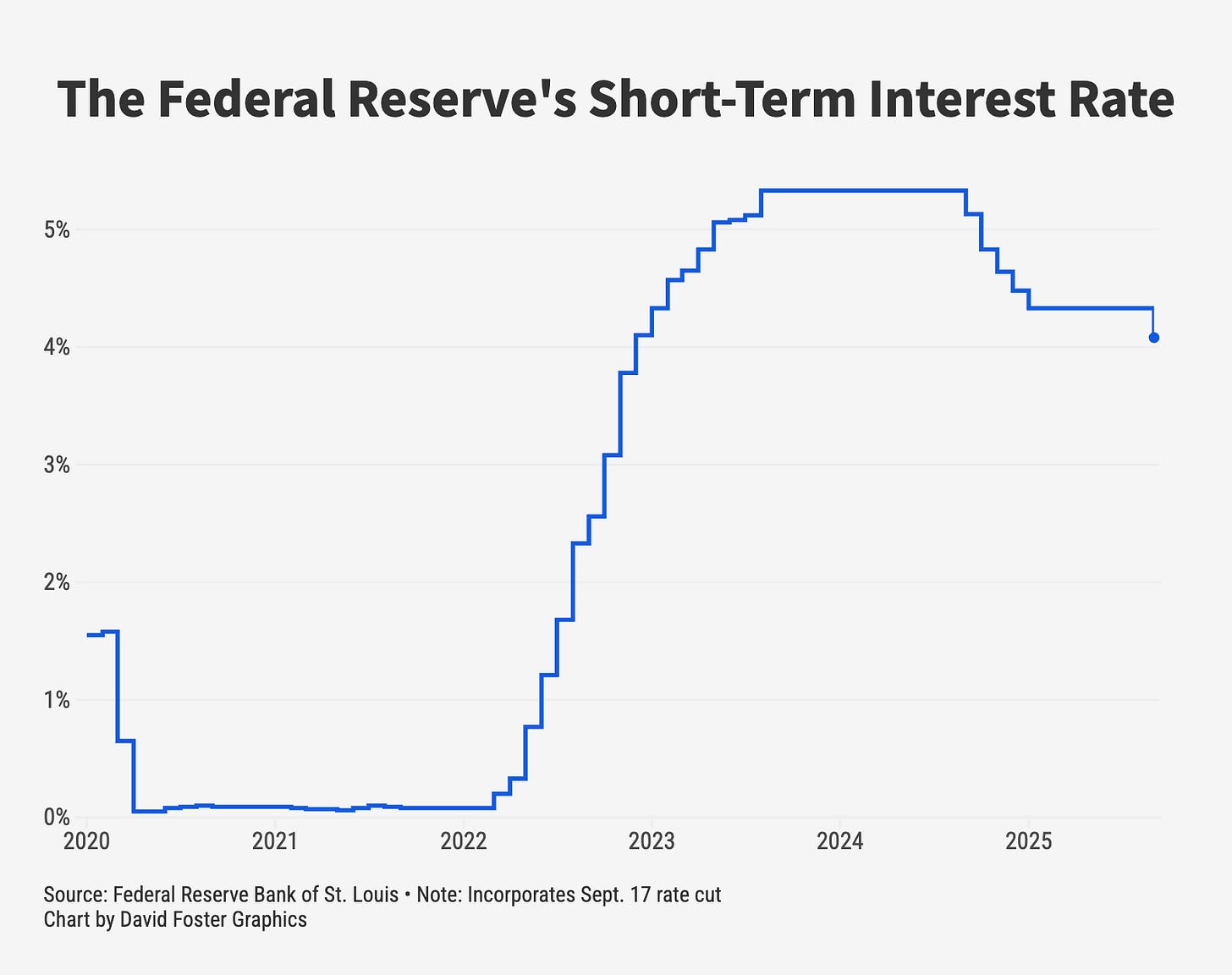

That pattern broke down last year, as you can see by squinting at the following charts constructed by graphics guru David Foster. The first chart shows the Fed’s short-term rate, which moves in stair-step fashion because the Fed sets a rate then maintains it for a period of time. From September to December of 2024, the Fed lowered short-term rates by a full percentage point, from 5.3% to 4.3%. [Geek note: Those are the Fed’s “effective” short-term rates, which vary slightly from the “target” rate, which is always in an increment of .25.]

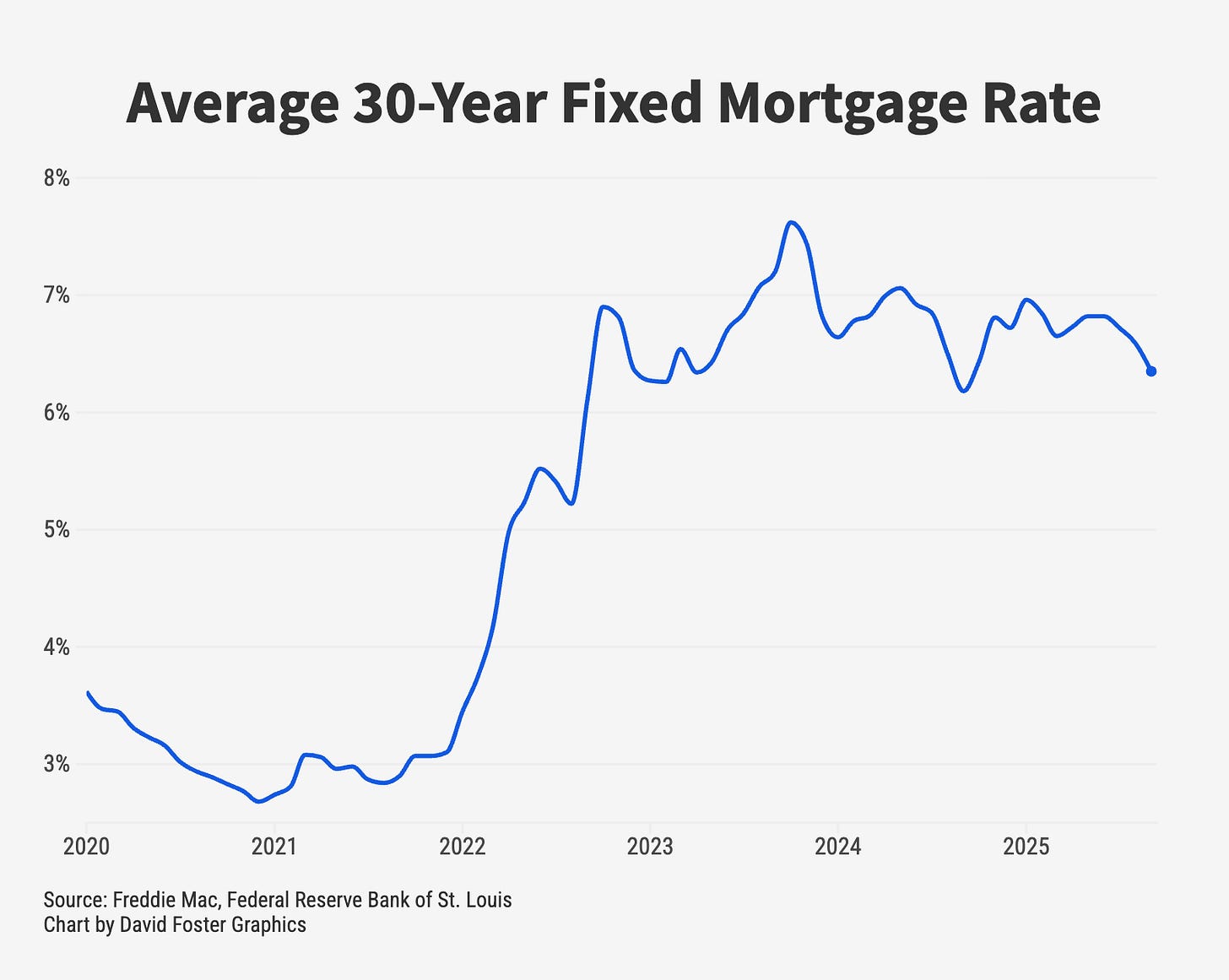

During the same period of time, the average 30-year mortgage rate rose by nearly a full percentage point, from 6.1% to 7%. So real rates paid by real people actually went in the opposite direction of the Fed’s short-term rate. That was an unusual occurrence driven by investor concerns about worsening inflation, higher rates in the future and the excessive amount of federal debt coming onto the market.

While the Fed can influence longer-term rates, it doesn’t set them directly. The market sets those rates, based on investor beliefs about future risks and the return they demand to lock up their money in a bond for 5 or 10 years, or more. That shows up directly in the interest rate on the 10-year Treasury, which is a benchmark for most business and consumer loans.

So when you hear that the Fed cut interest rates, that doesn’t mean it cut the rates you’re likely to pay for a mortgage or a car loan. It means that somewhere deep inside the financial system, money is getting cheaper. That can benefit the economy over time by spurring investment, hiring and economic growth, which is why the Fed does it. In this instance, the Fed is worried that a sharp slowdown in hiring and other signs of stress reveal economic weakness warranting monetary stimulus.

It's not all bad news for borrowers. Since the Fed doesn’t set long-term rates, they can fall without any Fed intervention—and they have been. Since January, the average mortgage rate has dropped from 7% to 6.4%. Rates are falling in part because investors expect lower rates in the future, and the Fed is playing into that. Investors may also think that a weakening economy will keep inflation in check, since that implies tightening wallets and softening demand.

Trump wants sharply lower rates as a kind of superstimulus that will offset the depressing economic effects of his tariffs and mass deportations. A quarter-point cut is movement in the right direction, so Trump’s relentless Fed bashing may ease up a bit. But Trump wants a full 2- or 3-percentage-point cut, which would be a crisis-level move that significantly raises the risk of higher inflation.

Trump has been able to appoint one loyalist, White House economist Stephen Miran, to a spot on the Fed’s policymaking committee. But he doesn’t yet have enough sway at the Fed to dictate interest rates. So unprecedented intrigue at the Fed isn’t yet hitting the real economy. If it ever does, that will be a story that’s hard to overhype.

And guess what long-term government rates (that mortgages are actually tied to) did today: they're up! (once again) Maybe it's an echo of last September when the Fed first started cutting short-term rates.

It's quite interesting too that Miran talked up the Fed's 3rd mandate in his confirmation hearing before the Senate last week. (What?! I thought there were only 2 mandates!) Well, Section 2A of the Federal Reserve Act lays out 3 mandates for the Fed, and that third one is "moderate long-term interest rates."

The bond market is arguably Trump's biggest problem this term, and we have a taste of where his unorthodox approach to policymaking might land next. If Cook goes, expect a full frontal attack on the Fed's "dual mandate."

You heard it here first.