Here’s what the delayed inflation report probably shows

There will be a flurry of coverage when the CPI report arrives on October 24, but we already know what it's likely to say.

We’ve now missed two key economic reports because of the government shutdown: the jobs and inflation data for September. Yet markets are humming along and economists still have a pretty good idea what’s happening with jobs and prices.

As I’ve written before, there’s a lot of alternate data that tells us basically the same thing as what’s in the official government releases. The job market was probably stagnant in September, with little or no job growth. Clues come from private data sources such as the ADP payroll report and the Indeed job-posting index, plus forecasts at many research and investing firms.

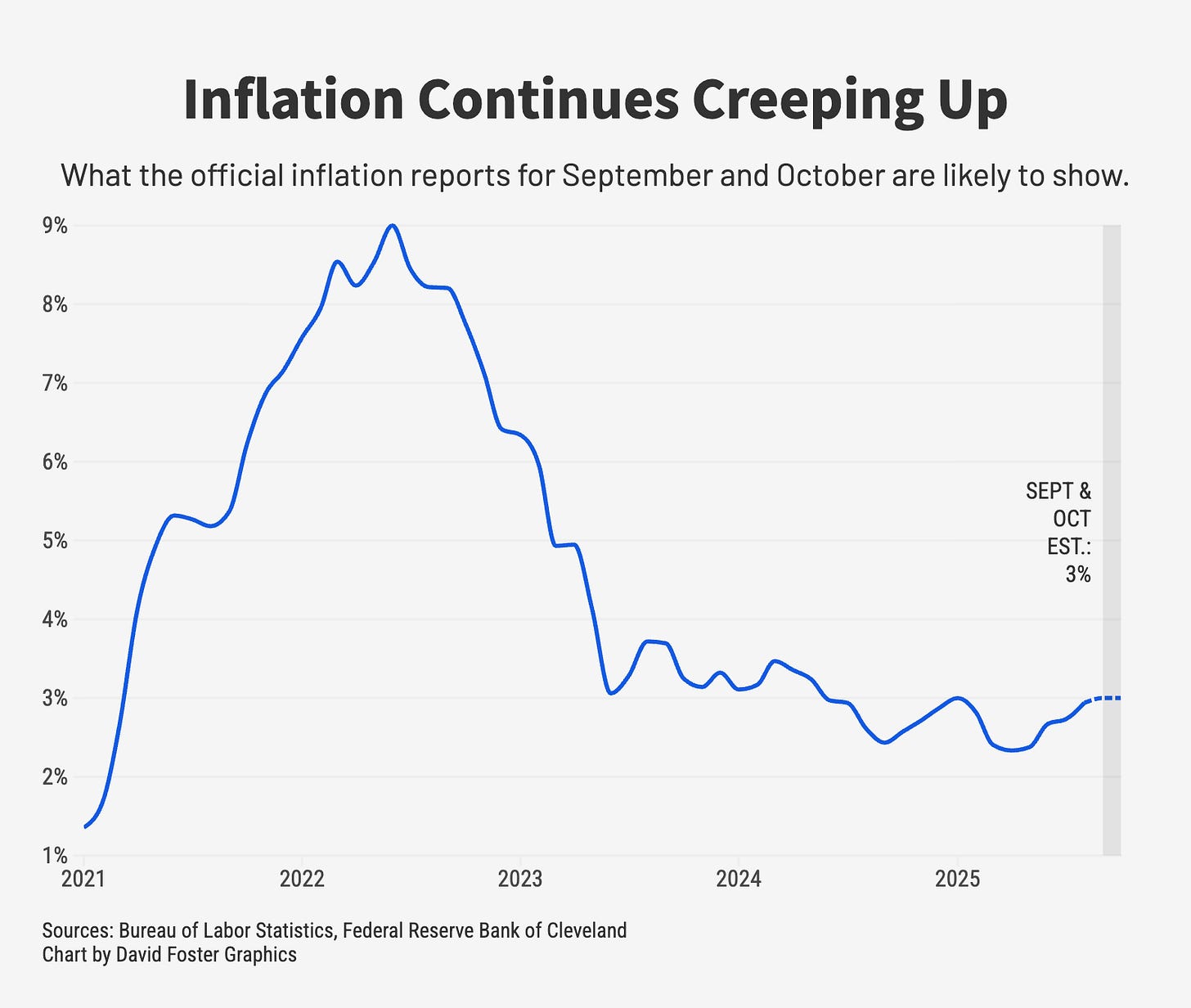

There’s similar alternate data for inflation, which can fill in the blanks until the government releases official numbers belatedly on October 24. The Cleveland Federal Reserve has a “nowcasting” tool that pegs the annual inflation rate at 3% in September, plus 3% in October. That would be a modest hike from the official 2.9% rate in August.

Research firm Morning Consult conducts an ongoing price survey that also puts the September inflation rate at 3%. Bloomberg’s survey of economists yields a 3.1% forecast. The Goldman Sachs outlook is 2.9%. Truflation is an outlier, estimating annualized inflation of just 2.2%. Here’s the chart by graphics guru David Foster, using the Cleveland Fed’s estimates for September and October:

Financial media will celebrate the return of the inflation report on October 24 like the arrival of the prodigal son. But for markets, it will probably be a non-event, given that investors have already priced in what they expect the news to be. Ordinary folks can glance at the headlines and, if the number’s in within a couple tenths of 3%, move along.

Inflation still matters. As the chart shows, inflation dropped consistently from the peak of 9% in 2022 to a low of 2.3% in April. That was almost back to normal, aka the Federal Reserve’s target of 2% or so. But inflation has been ticking back upward since then, largely because President Trump’s tariffs are making imports more expensive. That’s forcing consumers to pay more, while also cutting into profit margins at many companies.

For most consumers, the difference between 2% inflation and 3% is negligible, economically. But the psychology of inflation is a different story. When people think the president is doing something that makes ordinary products more expensive—as many voters do with Trump’s tariffs—they’re likely to blame him for any price hike they notice. They might pay closer attention to prices in the first place, if they hear that tariffs are likely to push them up.

There are a few key items inducing sticker shock these days, such as coffee, beef and bananas. Other prices are down, including gasoline and electronics, which is keeping overall inflation pretty moderate. But bad news always garners more attention than good, and surveys show consumers still feel punished by inflation.

Price levels also matter for the Federal Reserve, which has begun to gradually cut short-term interest rates. Lower rates can worsen inflation, one reason the Fed has waited to cut rates even as the job market weakens. And if the official inflation numbers at some point suggest that inflation is soaring once again, the Fed would probably put a halt to rate cuts.

For now, the Fed seems to have made peace with the Trump tariffs, on the grounds that they’ll generate a temporary blip in inflation that will fade by next year, or the year after. The story for now is that Inflation is a bit too high, but not high enough to break the glass. That probably won’t change any time soon.