There were no surprises on December 10, when the Federal Reserve cut short-term interest rates by a quarter-point, exactly as markets expected. Analysts parse every syllable Fed chair Jerome Powell utters after each decision, but we’re not going to bother with that here. You could argue that investors obsess over the Fed chair’s remarks only because they block off the afternoon every Fed Day and need something to do.

Here’s what is worth knowing:

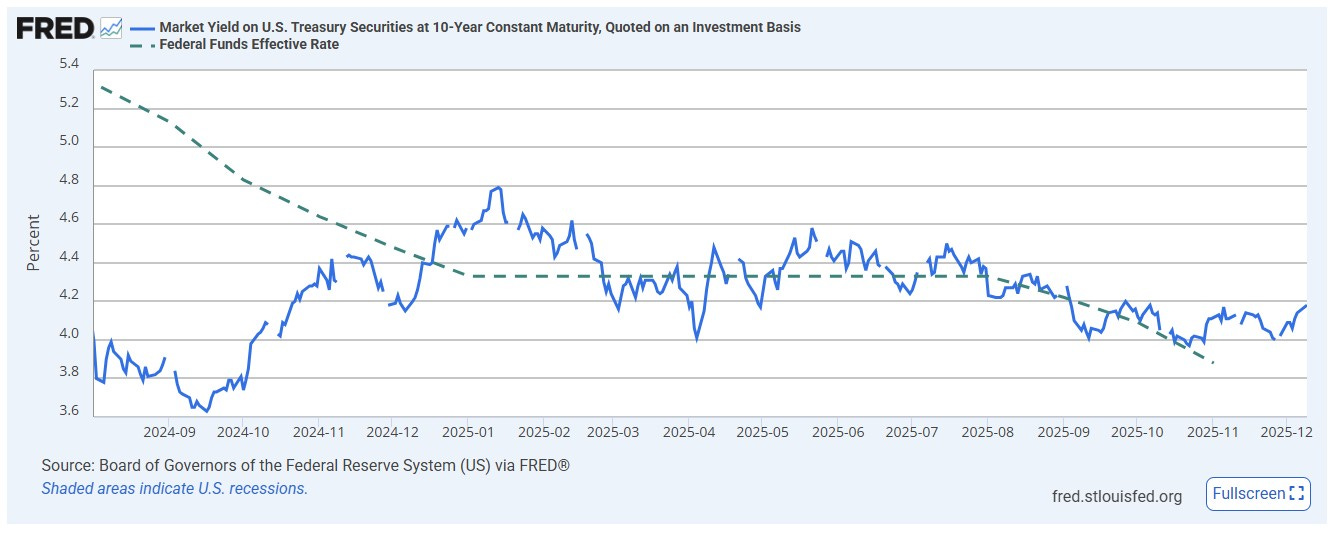

1. Short-term rates are drifting down, but long-term rates are not. The Fed has been cutting, on and off, since September 2024. Since then, it has brought short-term rates down by 1.75 percentage points. But long-term rates during the same time have risen by half a point, as the chart below shows. Most businesses care about long-term rates, such as the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield. Since September 2024, the 10-year yield has risen from a low of about 3.65% to about 4.16% now. The 10-year anchors the rate on mortgages, car loans, and most other loans ordinary people take out. Short-term rates mostly affect banks.

There are a few reasons short-term and long-term rates are going in different directions. Bond investors are worried about the massive amount of US government debt on the market, and also about inflation that might stem from the Trump tariffs. That could make holding longer-term bonds a little more risky, which means the rate has to be higher to entice buyers.

At any rate, investors are now focused on how many Fed rate cuts there will be in 2026, and the guess right now is either one or two. This probably won’t matter for ordinary borrowers. Most economists think the 10-year Treasury will stay around the range it’s in now, which means the rates on mortgages and most other loans will likely stay near where they are, as well. Short-term interest rates cuts can boost stocks for a spell—as they did after the December 10 Fed cut—which is good for shareholders. But most borrowers won’t get a break.

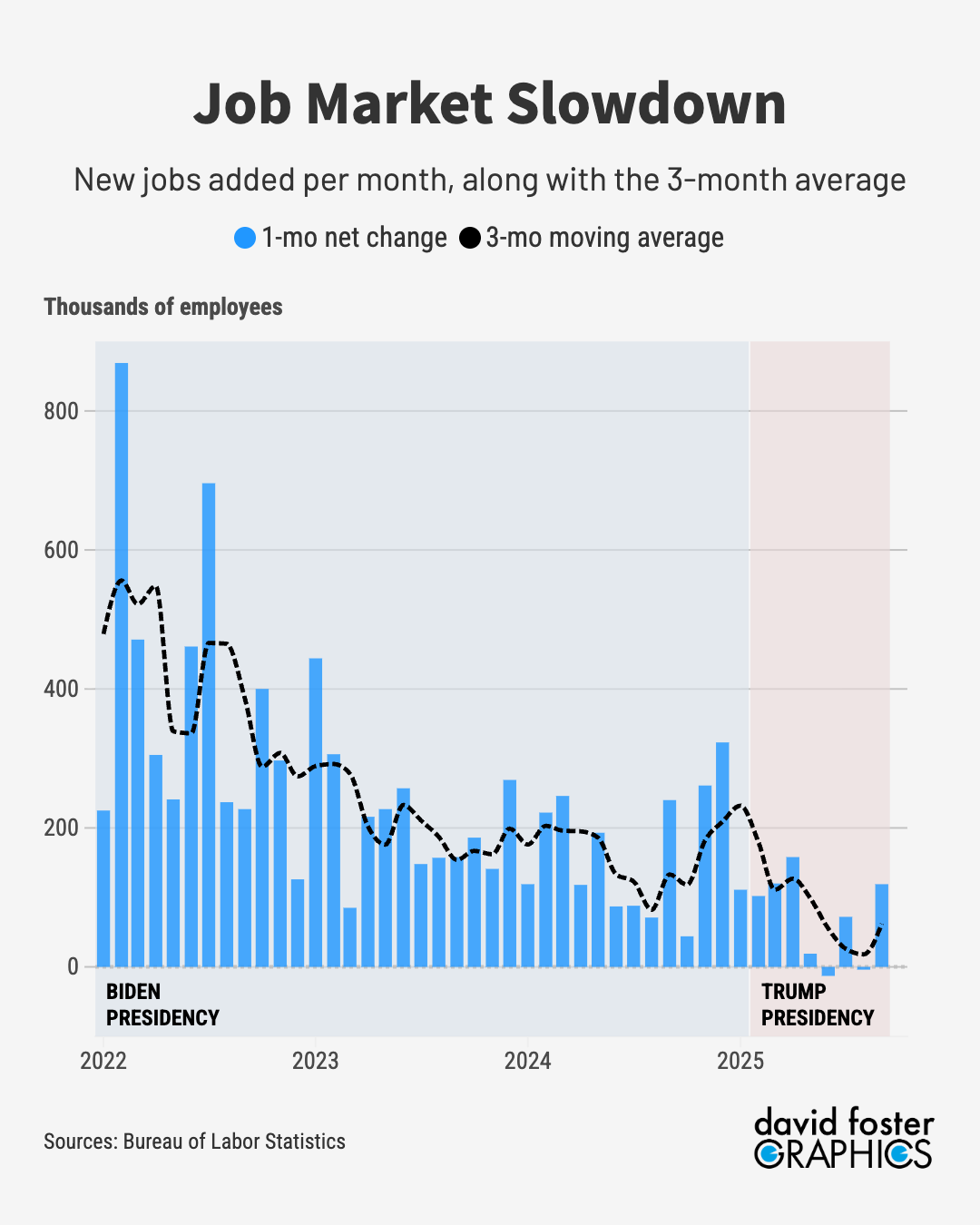

2. The Fed is worried about the job market. Some of the usual employment data is missing, because of the recent government shutdown. But Powell cited other data suggesting the job market may actually be shrinking. “The Fed realizes … employment is not cooling, it is contracting,” economist David Rosenberg of Rosenberg Research wrote in an analysis after the Fed meeting. “I sense this will continue into 2026.”

Powell is hardly the only one paying attention to a weakening job market. Consumer surveys show the same concerns and total employment actually dropped in two of the last four months for which there’s official data. Powell sees what many others do.

3. Trump hasn’t seized control of the Fed. Trump’s Powell-bashing has stoked months of speculation that he would try to fire the central bank chair and set interest rates from the White House, which would be a disaster for markets. It hasn’t happened. The Fed’s actions in 2025 are broadly in line with what a weakening economy with slightly hot inflation deserves. Analysts note that there was an unusual split in the December 10 vote, with two of 12 voting members saying there should be no rate cut, and one saying there should be a bigger cut. The Fed usually votes unanimously.

Eh, so what. The result is the same: a modest short-term cut that seems to be warranted by economic conditions. Now everybody needs to get busy trying to guess what the Fed will do the next time it meets, in late January.