Fed Chair Jerome Powell is getting a bit Trumpier

Few noticed, but Powell recently signaled that the Fed wants lower mortgage rates and other economic stimulants Trump has been pushing for.

President Trump is a fire-hose of insults and criticisms, and his latest barbs include familiar targets such as Joe Biden, Chuck Schumer and Kamala Harris, plus Zohran Mamdani, China’s devious trade warriors, and Time magazine’s photo editors. Even under the halo of a Middle East peace deal, Trump fires off his zingers.

But there’s been surprising silence recently regarding one of Trump’s most prominent perceived foes: Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell.

Earlier this year, Trump repeatedly mused about firing Powell, who presides over a powerful monetary policy committee that hasn’t been stimulating the economy enough for Trump. For months after that, Trump repeatedly hectored Powell for being “too late” to cut interest rates, calling him, among other things, “a stupid person” (which Powell assuredly is not).

But a funny thing has been happening lately: Trump has let up on Powell, as the Fed has started making exactly the kinds of moves Trump wants to see. The most obvious was a modest short-term interest-rate cut in September, the first in nine months. The Fed has signaled that a few more such rate cuts are likely.

Just as importantly, Powell recently explained that the Fed is likely to end an arcane but powerful program known as “quantitative tightening,” or QT, which has been in place since 2022. And that policy change would do more to lower real-world interest rates than the short-term rate cuts that get far more attention.

Lower long-term rates for mortgages, car loans and business loans are the real prize Trump is after. To Trump’s mind, they’d trigger a frenzy of spending and growth, lower the cost of financing the gargantuan national debt and earn praise from his friends in corporate America.

Quantitative tightening is the opposite of quantitative easing, or QE, which was a novel form of monetary policy the Fed launched for the first time during the financial crash in 2008. Back then, the Fed had already lowered short-term rates to 0, yet the crisis was so severe that the economy continued to shrink. So the Fed started buying huge amounts of mortgage-backed securities and other financial assets.

A huge new source of demand for those assets rapidly lowered long-term interest rates, because debt issuers could pay less to borrow and still find a buyer in the Fed. QE can be so powerful that when the Fed first announced it in 2008, long-term rates fell 1.07 percentage points in just two days.

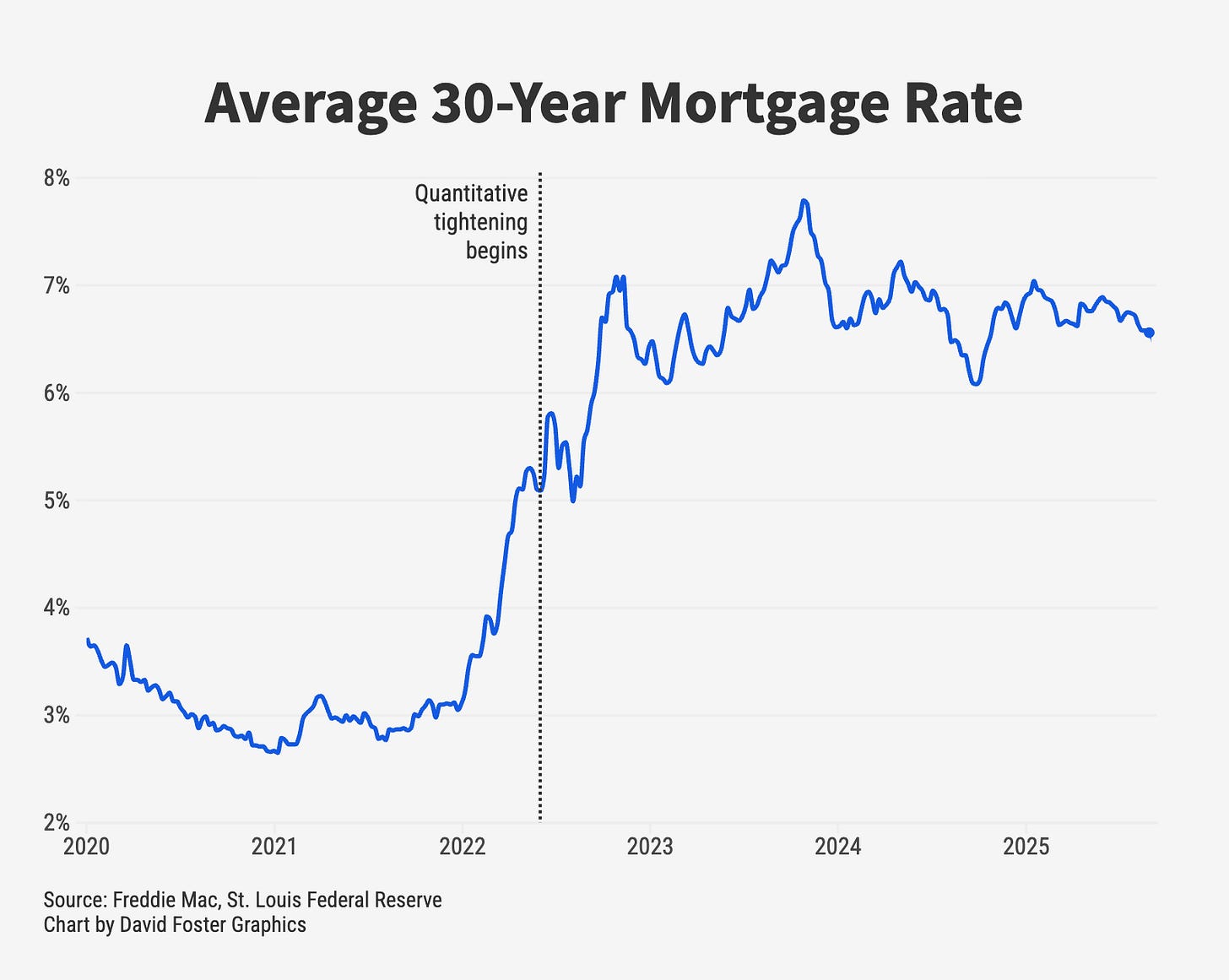

The Fed executed four rounds of QE through the Covid pandemic in 2020. QE was a major reason mortgage rates his record lows in 2020. That was great for homeowners able to refinance and save thousands of dollars per year. But artificially low rates also distort markets by juicing demand for credit and the stuff it finances. One result was the surge in home values that’s a big cause of the housing affordability crisis today.

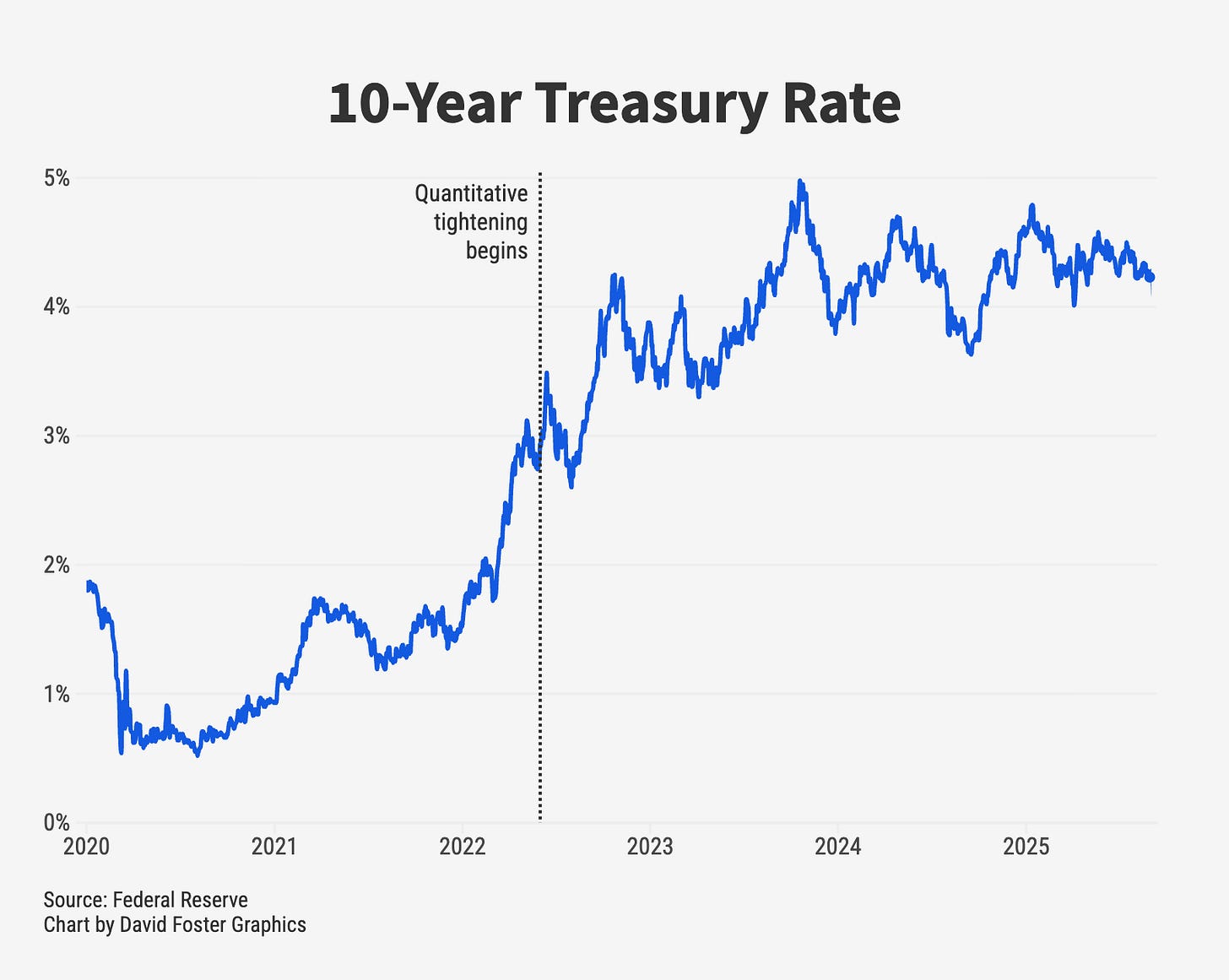

The Fed switched from QE to QT in 2022, which means it went from buying or holding a steady amount of financial assets to letting those assets mature without replacing them. That began a slow reduction in the value of assets held by the Fed, which as expected, pushed up interest rates. Longer-term rates rise under QT because the Fed is no longer a huge buyer, which means issuers have to offer higher returns to sell their debt.

Since the Fed began QT in June 2022, the rate on the 10-year Treasury has risen from 2.94% to 4.05%. It got as high as 4.98% in October 2023. Mortgage rates, which closely follow the 10-year, have risen from 5.1% to 6.3%, while getting as high as 7.8%, also in October 2023. That’s what the Fed wanted. It was fighting inflation that peaked at 9% in 2022, and higher rates crimp lending and spending, which helps get prices under control.

In an October 14 speech, Powell used a bunch of banker-speak to basically say QT is winding down. “The end of QT is upon us,” economist Peter Boockvar translated in his newsletter the same day. Powell’s remarks didn’t generate the frenzy of news coverage that follows every one of the Fed’s scheduled meetings, where policy changes are usually telegraphed so effectively that journalists often prepare their stories in advance. But Wall Street noticed right away.

Goldman Sachs published a research note after Powell’s speech saying it was changing its forecast for the formal end of QT from next March to next January. Goldman highlighted Powell’s concerns about a weakening labor market and other signs of a slowdown, which would justify a move to ease up on long-term rates and stimulate some additional spending.

This doesn’t mean that Powell or the Fed are caving to Trump’s demands. What it does mean is that economic conditions are gradually leading the Fed to implement the easier monetary policy Trump wants. The 10-year Treasury nearly hit 5% at the start of the year, a level that might signal stress in financial markets. But many forecasters now think it will stay anchored near 4% and some think it will drift below that. If so, mortgage rates might dip below 6%.

Trump may not be satisfied. He wants the Fed to cut rates by 3 percentage points or more, which would be a drastic move typical only in emergencies. The Fed’s gradual pace, meant to keep markets stable, may be way too slow for Trump.

By continually faulting Powell, Trump has also tried to tee up the central bank chair as the blame-taker if the economy tanks. Trump, in his own mind, has no reason to make nice with Powell, whom he may need as a fall guy.

But Trump hasn’t been trashing Powell lately, either. On September 15, he complained that the quarter-point rate cut the Fed announced that day wasn’t big enough. Since then, there’s been essentially no peep from Trump on Powell or the Fed.

The Fed’s next official meeting concludes on October 29, when it is likely to cut short-term rates by another quarter-point. Trump will probably complain once again that it’s not enough. But if it’s quiet up till then, consider it a sign that Trump and the Fed are slowly converging.